Rachel Stanley: Into The Landscape

Rachel Stanley (b.1996) has been rooted in the Scottish art scene since she arrived to study at Edinburgh College of Art in 2021. Fusing elements of the landscape and the human body together, melding abstraction and figuration, Rachel has developed an intriguing visual language which is quite remarkable in its strength and resolution. In conversation with the artist, Douglas Erskine gets a sense of Rachel Stanley’s exciting, evolving practice.

Rachel Stanley casts a wide net. She has studied the painters of the past and the present. She has studied the stuff of human anatomy and natural geology. She has experimented in the studio, refining her process – and she has gone out and absorbed the sensory riches of immersion in the physical landscape.

She has an acutely keen eye for texture, form and colour, whether she recognises them in a fine painting, in the furrows of a rock face or in the deliciously glassy patterns of a coursing river. These are the things which might stop her in her tracks.

Rachel’s keen eye, her natural curiosity for the visual world and her enthusiasm for the life of a working artist explains this quite unusual breadth of engagement. But she is very selective in what she accepts as her influences and strikingly mature in her means of expressing them. In her work, many disparate elements and many considered lessons coalesce. The results, big or small, on canvas, calico or burlap, are intelligently-made and deeply-felt.

In her hands, abstraction and figuration appear as symbiotic forces, not opposing ones. The lessons of abstract painting breathe life into figuration, which might otherwise run the risk of looking academic on one hand or twee on the other, perhaps. The lessons of figuration ground work which might otherwise be called abstract with a real-world weight. Rachel roughs it all out in the process of making, striking a balance in work which sees the human form mingle with the landscape and vice versa.

Douglas Erskine spoke to Rachel about the creative course she’s charted so far, getting to grips the forces which drive the creation of her distinctive visual language.

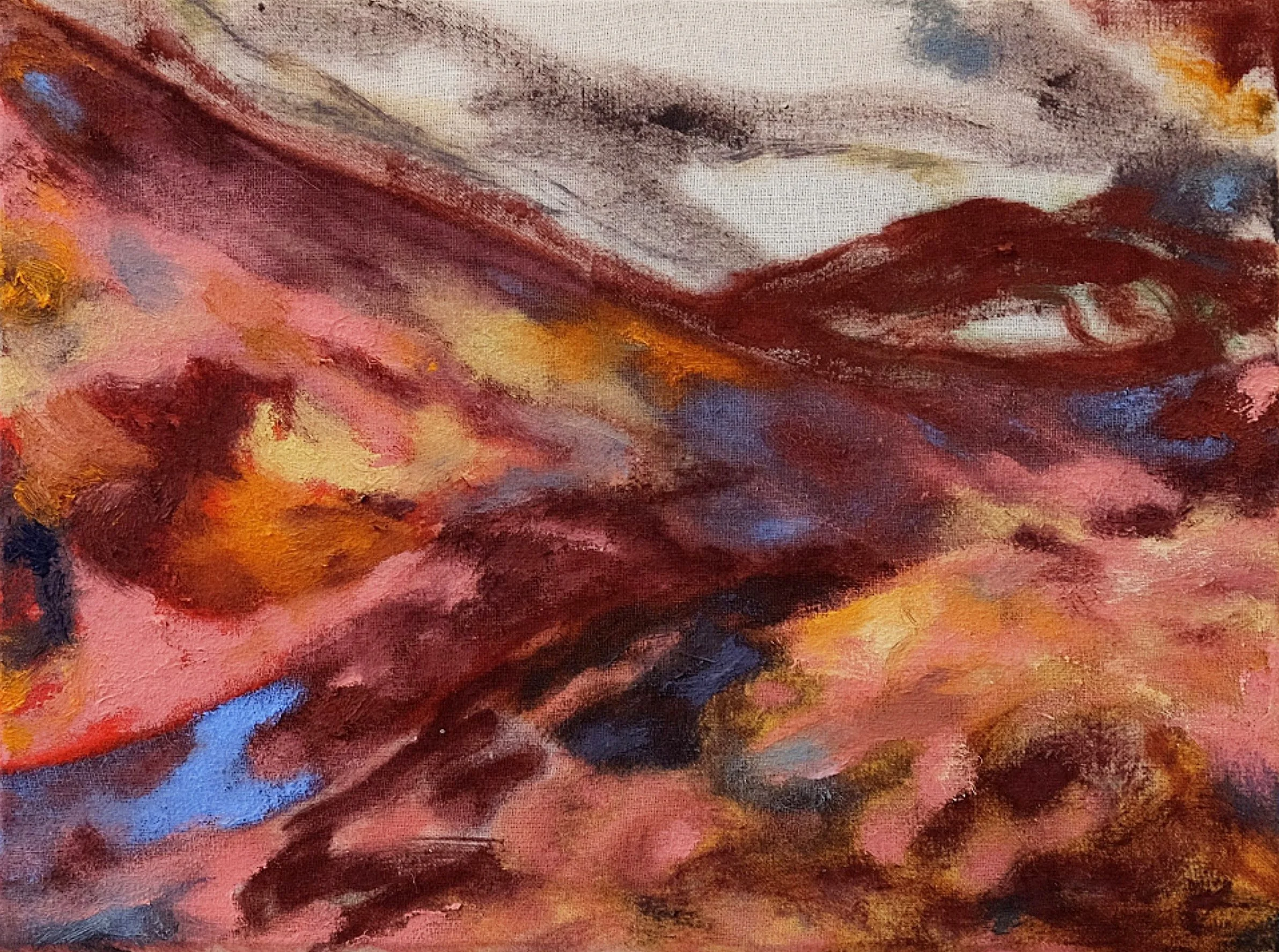

Rachel Stanley, Headland Shape. Oil and oil pastel on canvas. 90 x 80cm. 2022. Private collection.

Rachel, I’ve always been struck by the way you manage to synthesise figuration and abstraction in your work - is this an approach you’ve developed consciously these past years?

Thank you. When thinking about my approach it’s relevant to note that painting was a practice I shifted into from photography, which I pursued for many years prior. My entry into the world of painting was quite a symbolic departure from the professionalism and objectivity I found in my previous field. Through trying to work professionally, I specialised in architectural photography, which enabled me to work in relative solitude and to capture design in an artistic way, often with natural light. In the end, though, I felt stifled by the client-driven process of image-making. It is a place where objectively “good” and “bad” images do exist. There are very formulaic rules of composition to be followed. It all felt very distant from my ideas of what it meant to work creatively.

At this time I took on a studio space to use as an editing suite for my pictures. However, paralysed by the fixedness of making lines straighter on Photoshop, I started drawing circular compositions instead. It was all very basic – making gestural, meditative drawings using printer paper and a graphite stick – but felt very freeing, and so things developed slowly from there. This is the “symbolic departure” I mentioned – I never needed to create accurate representations of things, because then I could have used a camera. It made sense for me to pursue these more abstract approaches in alignment with how I see the world. I like to keep my cards close to my chest – almost creating a visual language of my own, then using representational elements and titles as clues for the viewer. For this reason, I wouldn’t say the work ever felt entirely figurative.

Rachel Stanley, Asleep. Oil on canvas. 50 x 70cm. 2021. Private collection.

We could point to many works which reflect the strength of your visual language. A painting like Asleep, from 2021, is a successful figurative picture but it has a freedom and intuition which suggests you’ve been alive to the possibilities of abstraction for some years. It strikes me as an important work in your developing identity as a painter.

To me, it doesn’t feel too different from the other works I make, as it plays with the same themes – flattening of space, unusual perspective – and it uses the same palette. The more apparent figuration perhaps creates a clearer sense of symbolism, whereas in my landscapes it’s more embedded.

Asleep is unusual for its more domestic setting as well as the obvious presence of a figure. I don’t tend to paint figures, although there are traces of people in all my landscapes. After all, what we call “landscapes” are in reality very curated and controlled environments. For some reason I’m not interested in a person-centric image (often offered through figuration). I’m much more interested in an approach I could describe as “deep time” – an expansive, anti-anthropocentric perspective.

However, I do keep coming back to Asleep. I think it relates to how I was feeling at the time in an interesting way – maybe that’s why people seem to like it. Perhaps it feels more honest.

Rachel Stanley. Down by Siccar. Oil on board. 17.8 x 12.7cm. 2024. Private collection.

You’ve cast a wide net these past years, drawing together very broad-ranging influences which find fantastic expression in your work. Who or what has affected you?

Graham Sutherland’s landscapes are very significant. There’s a real ease of making there and a freedom from tradition. The book An Unfinished World (George Shaw), which accompanied an exhibition of his landscapes, is wonderful. I’m also deeply drawn to Joan Eardley - the urgency of the work, her dedication to painting outside in Catterline in all weathers. And there are many other artists I hold dearly - Eva Hesse, Louise Bourgeois, Pierre Bonnard, Edvard Munch…

I would be remiss not to mention my ex-partner, James Owens [a fellow artist], as a very real influence. I learned to paint through watching him; when we first got together, he was at Camberwell, so I absorbed a lot just through experiencing him playing with ways of making. At that time I wasn't yet painting myself, but I’m confident that watching him fed me a lot subconsciously. He was also incredibly motivating when I was learning to draw; I'll always treasure the support I had from him in those early days as it really kept me going.

At present, my direct experiences with the landscape are my greatest influence. I am finding myself picking up my book Geology and Landscapes of Scotland (Con Gillen) more frequently than any monograph.

Rachel Stanley. Path. Oil and oil bar on calico. 18 x 24cm. 2022. Private collection.

Recently, your experiences in the landscape have been all-important?

I must say a significant shift in my practice occurred when I got my first car late last year. I’ve been able to spend much more time and energy in the landscape - to really see it for myself, rather than using reference images or imagination. Geologically, the Scottish landscape is so dynamic, with such a varied sense of “deep time” across a relatively small area, arguably the best in the world.

It’s important to see this first-hand, and the time I spend exploring helps me build a sort of “mental map” of the shift of the landscape across the country. Sometimes I don't even need to stop the car - just absorbing through driving directly through the landscape is very invigorating. I also stop off and walk, make drawings and rubbings, take photographs, et cetera, which can be referenced later back in the studio. These drawings often feel like works in and of themselves, but are pretty small, so sometimes they deserve to move across into paintings of their own, to take up a bit more space.

Rachel Stanley, Climbing The Gorse Hill With You. Oil on wood panel. 20.32cm x 25.4cm. 2025. Private collection.

You manage to fuse the forms of the natural landscape with elements of the human body. It’s a difficult approach to navigate – like the balance you strike between abstraction and figuration – but you meld these forms with striking maturity.

I’m interested in probing perspective - looking above, below, through, in-between - as a counter to the human eye, which is seen as the standard viewpoint. I like to think about what it would be like to look directly into a body and see the shape of a cell, or deeper through the landscape and into the rock itself. The fact that I can do this is the joy of painting.

I’m very interested in contrasting the transience of human existence with the fixed state of the landscape. I want to contrast these elements of human and non-human time. I also want to highlight the multitude of parallels in nature – such as the presence of a spiral shape. By abstracting elements of form and shape in the making process, I want to suggest the existence of multiple truths in the work. An image doesn’t have to depict one single thing - I really like it when different people each pick out a different element of my work, often finding shapes or meanings that hadn’t occurred to me. It’s important for me to make work which feels free from the binaries of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. Following these principles allows me to use painting to calm something within– as an antidote to sensory overload, and to make sense of a world which is often very overwhelming.

Rachel Stanley, Look (Under, Over, Through, In-between) II. Oil on calico. 30 x 40cm. 2022. Private collection.

These are works which are charged with something deeply personal. But there is an immediate sensory weight, wrought all over the surface of your pictures, given your handling, which touches other people too. That sensory connection might allow them to share in what you yourself feel.

I aspire to encapsulate a subject in a way which is more than just visual, but has some other sensory element to it. I suppose that’s the neurodivergence creeping into the process.

Materiality is a big component of how I make, as the materials shape the way the work is made and ultimately, they decide how it ends up. For example, marble dust adds texture and grit, and if I add the dust while the painting is laid out flat on the floor, I can pour thinned paint on top in more of a staining process. Using calico in place of canvas feels more delicate - it creates a smoother surface as the weave is smaller compared to canvas, so paint glides along the surface beautifully. However, it's also less forgiving with regards to layering and correcting mistakes is more difficult.

In this ‘push and pull’ process, I often start with an image in mind, but the act of making means things shift over time. Often it feels like the paintings are making themselves; I’m just there to conduct. The act of painting feels like an enquiry into this process, rather than trying to achieve anything which feels too masterful. Materiality always wins.

Rachel Stanley. M.U. Oil and marble dust on calico. 20 x 30cm. 2023-24. Private collection.

The strength of Rachel’s vision, carried off in her compelling visual language, brings a striking vision to bear. Across her body of work, she forges a relationship between the unsettled, ever-changing human body and the fixed, objective landscape. In her hands, something so intimate and something so remote fall together in a natural rhythm. The world she creates is congruous, harmonious and comforting. These are the qualities which chimes throughout her body of work, and which continue to find form in an exciting, evolving practice.

Douglas Erskine

Rachel in her studio, 2021. Photograph by Lucy Copeland-Tucker

Acknowledgements:

With many thanks to Rachel Stanley.

Photographs of Rachel by Lucy Copeland-Tucker. All other images courtesy of the artist.