Patrick Hennessy & W.P Vannet: The Baird-Patrick Boys

Patrick Hennessy is regarded as one of the leading Irish artists of the twentieth century. He exhibited two paintings at the RSA in 1939. William Peters Vannet exhibited 75 works at the RSA between 1939 and 1984. They grew up in Arbroath around the same time. Neither feature in many Scottish art surveys. Roger Spence investigates, starting with an exhibition in Arbroath in 1938.

On Saturday 16th July, 1938, a group of artists, art enthusiasts and dignitaries assembled at the Arbroath Library to celebrate the opening of the first of a new series of exhibitions organised by the Library Committee in the Art Gallery.

Arbroath in the 1930s was a hard working industrial town with a very active fishing port. It stood in triangulation with J.M. Barrie’s Kirriemuir/Thrums kailyardism and McDiarmid’s Nationalism and Scottish Renaissance in Montrose. Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s Scots Quair contrasted the rural life of the Mearns with the urban rags and riches of places like Arbroath and Dundee.

Arbroath had a sketchy art history but there was momentum. Having been home to some notable artists, including, briefly, Aikman, Middleton Bell, Helen Chapel, Herald, Henry T Wyse and Colin Gibson. Joan Cuthill and George Grassie were sixteen year olds in 1938, showing great promise. William Littlejohn, Morris Grassie, Irene Halliday, and Ken Roberts were all youngsters in the town.

The industrialist, James Renny had bequeathed the town an Art Gallery and some quality paintings, including one by Pieter Breughel, on his death in 1876, and after a period of stagnation, a small shift in political personnel was a factor in re-starting an exhibition programme (Note 1)

The legacy of James Watterston Herald (1859-1914) remained strong. The visitors that day would have walked past Herald’s memorial tablet on the wall up the stairs from the Library. The only visit to Arbroath by a serving UK prime minister had been (and still is) Ramsay MacDonald’s visit to the Library in 1924 to formally unveil the plaque and speak eloquently in tribute to Herald - a memorable moment in Arbroath’s history.

William Banbury, James Watterston Herald, memorial tablet, Arbroath Library

J.T.Ewen, the former Inspector of Schools, who had supported Herald throughout his life, had been, along with the Dundee architect, Charles Soutar, the prime mover in persuading MacDonald to come to Arbroath. And it was Ewen, now aged 76, who was on the Art Gallery stand again on that July Saturday. He had presumably persuaded Sir Harry Hope, also in his mid 70s, Vice Lieutenant of Angus and former MP for Forfar, to come down from his ‘seat’ at Kinnettles House to open the Exhibition. Ewen, who also travelled from his home in the Forfar area, at Pitscandly, was well known in Arbroath, especially for his artistic engagement with Herald and Henry T.Wyse, and his over-40 year support of the High School art department. Thirty six years earlier it had been Ewen who invited the Duchess of Sutherland to visit the department and hosted her day in Arbroath.

Along the road at Hospitalfield, Arbroath’s Provost, William Chapel, had been a key player in the reopening of the institution as a postgraduate residential centre in the previous year, 1937, and in employing James Cowie as warden. In July 1938 Cowie had ‘An Outdoor School of Painting’ on an easel. Two of that year’s student intake were featured in the painting: Robert MacBryde and Waistel Cooper.

James Cowie, An Outdoor School of Painting, oil on canvas, 86 x 165cm, 1938, courtesy of Tate Britain

Perhaps Cowie was amongst the assembled group at the Library (he’s not in the press photograph!), as it would have been a high point in the Arbroath art calendar. He would certainly have been invited. I’d place a strong bet that Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun - ‘The two Roberts’ - would have been there. Perhaps Robert Henderson Blyth, Waistel Cooper and John Laurie, also resident at Hospitalfield that summer, would have come, as perhaps might have William Gear, an occasional visitor through the summer..

And the centre of attention that day were two very young artists from Arbroath, Patrick Hennessy (1915-1980), aged 22, and William P. Vannet (1917-1984), aged 21. They were both from relatively humble backgrounds, and both had lost their fathers in the first world war shortly after they were born. Their mothers had re-married and moved to Arbroath, with Hennessy moving from Cork and Vannet from Carnoustie. Both of them had grown up in the town, had been Duxes in Art at the High School and then attended Dundee College of Art. Hennessy had completed his Diploma Studies that year. Vannet had a year to go. They were both highly skilled draughtsmen at an early age and their work was underpinned by close observation and tight-lined representation. That’s where the parallels stopped.

What could be seen in the Gallery? The only photograph is one of sixteen dignitaries arranged on the steps of the Library. Provost Chapel was otherwise engaged on his way to the King’s Garden Party at Buckingham Palace. Harry Hope is identified and J.T.Ewen is front centre, with, presumably, Councillors and members of the Library art sub-committee. There is no sign of the artists or their work.

Arbroath Herald photographer, Art Exhibition opening, Arbroath Herald, 22nd July 1938, J.T.Ewen is front row, third from right, Sir Harry Hope, front row, second from right.

The Arbroath Herald reported: “The exhibits cover a fairly wide range both as regards subject and medium. Mr. Hennessy’s pictures are mostly in oils, in which his still life and self studies are particularly good. His flesh colours and backgrounds in the latter work call for the highest praise. Very pleasing too. are two small woodland pieces. Mr Vannet also shows some fine still life, a specially good one being of nautical objects. Two good portrait studies are noteworthy, while his water colours make a definite appeal, these including one or two foot-of-the-town sketches which are bright and original in treatment. The extent and variety of the exhibits make the whole display a distinctly attractive one.”

The Dundee Courier, reporting on the opening, said: “Mr Hennessy's exhibits are mostly in oils, and his still-life and self studies are particularly praiseworthy, Mr Vannet includes watercolours, oil paintings, woodcuts, and designs.”

It would be marvellous to see an illustrated catalogue, or even access a list of works from the exhibition, but there’s no record of one existing. We can make some educated guesses based on Hennessy and Vannet’s artistic paths from here on, as both were strongly influenced by their different art school experiences, but also their backgrounds and characters.

In the late-30s, Dundee Art College art department, headed by the perhaps underrated John Milne Purvis, employed two part time teachers of note who were close friends, James McIntosh Patrick (1907-1998) and Edward Baird (1904-1949). Whilst both would have shown young artists their commitment to detailed observation, draughtsmanship, and ways of experimenting with their empirical recordings, it is clear that Vannet was in thrall to Patrick, whilst Hennessy, who would never admit any such influence, took much from Baird.

Patrick and Baird had met as students at Glasgow School of Art. They arrived there on the same day at the same digs, both of them having been granted direct entry into the second year class of the diploma course because of their youthful competence. They shared common artistic interests and approaches. They both admired classical and especially Italian renaissance painting, they both worked slowly and painstakingly, applying themselves to a formality in planning, rooted in patience and an inquisitive, almost scientific, eye, which demanded that detail be collected, stored and presented.

There was no mood or impression in this method. They came back to the work day after day and applied themselves to the form, structure and concentration that was already established. And what they saw was always in the cool low brilliant light of the North East; a light that, especially in the six winter months, accentuates strong lines, and intensifies the contrast of sunned and shadowed.

They had no interest, it seems, in the bravura painterly approach of the Glasgow Boys-to-Colourist period that dominated Scottish art in the 20s. Both were fascinated by the work being produced by James Cowie (1886-1956) from his home and school in Bellshill. Cowie had grown up with the stark light of Aberdeenshire, loved Piero and Cravilli, and like Baird and Patrick, had absorbed the teachings of Maurice Greiffenhagen, who taught on a part-time basis at Glasgow School of Art from 1906 to 1926.

There’s another commonality between Baird, Cowie, and Patrick. If you sit in the opening room of the National Gallery’s Scottish wing and look at Cowie’s 1925 “Yellow Glove” alongside all the other paintings of that era, but notably J.D.Fergusson’s portrait, thick with solid paint colour and employing bright red lipstick, it is Cowie’s colours that zing from the wall. They are helped by the gloss of their finish, but it the intensity of the painting at the core of this visual impact. And up a few stairs Patrick’s “Stobo Kirk” knocks Cowie out in the colour intensity stakes: there is almost nowhere in the painting where the eye can relax. And Baird could do the same just painting blades of grass.

Ian Fleming (1906-1994), who was in the same year as Baird and Patrick at Art School, had grown up in Glasgow, and his sense of light was always different, more diffused, confused by cloud and smoke. He loved etching and painting scenes looking straight into the sun, as though it was a special moment. In Dundee and Montrose, there was more sunlight, westerlies having unloaded the clouds and rain over the west, and Patrick and Baird were also used to weeks of anticyclonic blue skies.

Internally, Fleming’s 1938 double portrait painting of the two Roberts shows much looser handling than the early portraits by Patrick and Baird. And he sets them in a relaxed pose; quite different to the attentiveness of Patrick and Baird’s subjects. Fleming was living in the moment. In their early years, both Baird and Patrick were approaching their work as though they were in Northern Italy in the fifteenth century with a host of assistants in their studio who could copy their master’s instructions. They couldn’t possibly paint on the scale they envisaged with the polish of the fine-brushed technique they were using. Patrick figured out a way forward. Baird was more stubborn.

Patrick Elliott (Note 2) reports Fleming’s description: “Baird would think nothing of looking at a drawing for half an hour, add a single pencil mark, and then sit back and examine it once more” and he passes on a comment from Patrick: “…if Baird were painting an object - for example a gun - then he would feel it necessary to acquire a detailed knowledge of guns. He would happily spend weeks studying them, and weeks painting them. And while the other students were progressing onto ever larger canvases, Baird's tended to get smaller.”

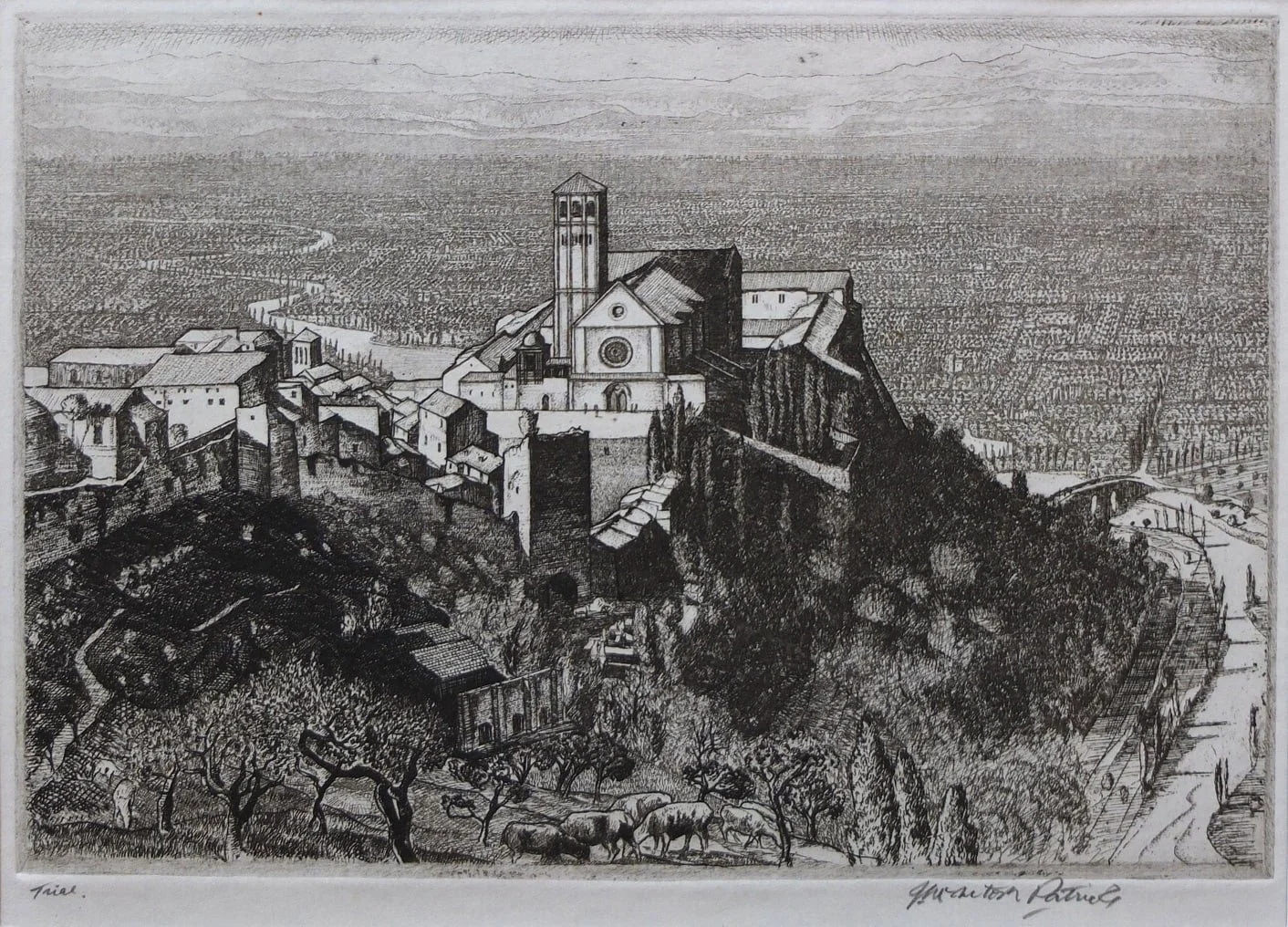

James McIntosh Patrick, Assisi, etching, 141 x 102cm, c.1934

Patrick’s father worked for the aforementioned Charles Soutar, and Patrick worked in Soutar’s architect’s office in his youth, adding perspectives and colour to architectural drawings - just as Herald had done a few years before in the same office. Roger Billcliffe reminds us that Patrick’s first influences were Herald and Melville. (note 3) He had started on etching when he was 14 and acquired professionally proficiency before he went to art school. He was also painting in oils at his Dundee school, Morgan Academy. Baird studied at Montrose Academy and as Jonathan Blackwood points out, his fascination and application to still life and drawing accuracy meant that he could draw the shells and bust used in his famous Birth of Venus (1934) when he was a teenager. (note 4) His father was a sea captain and away for long periods of time. His father’s death in 1923 in Australia was probably a contributing factor in Baird not arriving at GSA until he was 20, but he suffered badly from asthma, another limiting factor.

Whilst Patrick and Baird shared the same ideas, they had different attitudes towards work, opportunities and taking chances. They were both thinking hard about their work, but Patrick was able to create opportunities for himself and take them, in a way that Baird found impossible. Baird set standards for himself that meant he could hardly ever complete a work. Patrick took on an etching contract with a top-level London print publisher whilst he was a student that gave him a guaranteed income of £200/year (£15,500/year in today’s terms) on the basis that he produced a quantity of etchings. He had to complete, if he wanted to buy and run a car.

Patrick’s print contract smoothed his entry into the professional art world. With this and income from commissions of drawings of local landmarks by the Dundee Courier, and national landmarks by Dundee postcard publisher, Valentine’s, he was able to transition into the oil painting of the real and imagined landscape amalgams that won him a huge reputation in the 30s. Meanwhile, Baird used his travelling scholarship money from GSA to visit Italy and then returned to Montrose where he lived with his mother. He had very little income, but refused to finish paintings and most of the ones he sent to the RSA annual shows were marked ‘Not for Sale’.

Edward Baird, The Scottish Fifie Boat, watercolour on paper, 22 x 17.5cm, 1936, private collection

1212Baird has been portrayed as a bit of an austere recluse, but he was a very engaged member of Montrose social and cultural life in a period of heightened activity in the late 1920s and 1930s, with Fionn McColla, Hugh McDiarmid, Violet Jacob, and William Lamb amongst his many local friends. After his death in 1949, one of these friends contributed an anonymous appreciation to the local press:

“…though illness levied a terrible toll on his output, so that his achievement cannot be fairly measured against his forty-four years, it did not quench the vigour and keenness of his intellect and the courage and cheerfulness of his spirit. His conversation was a tonic to those who might have been expected to need one far less than he did. He discoursed with such wit and with such a droll turn on every subject that one hardly realised that his knowledge was truly encyclopaedic. His observation of men and affairs was penetrating and his summing up could be devastating, but it was not venomous. He truly loved his native town and people without expecting them to conform to the high ideals of which his criticism was an expression. As soon would he have expected his life to follow the pattern of his own desires. He had his own consolations, a devoted household, friends, and was content. We have our memories and must be content also.”

Baird and Patrick had a bond beyond art. Patrick asked Baird to be his best man at his wedding to Janet Watterston in 1933. And yes, Janet was related to James Watterston Herald: her father was his cousin.

Patrick was employed on a part-time basis in 1930 by Francis Cooper, head of Dundee College of Art. They had just been granted the ability to award a Diploma in Art, and throughout the 30s were heading towards a new independent status with monies left in the will of Mr. Duncan of Jordanstone. Six years later, it seems clear that it was Patrick who put forward Baird’s name to join the staff in 1936.

Baird worked there alongside Patrick for three years. It was a short-lived period, but the students had access to two powerful artistic minds, both of them deep-rooted in a classic tradition, with a clinical eye in observation, and with the drawing accuracy that produced detailed and accurate representation. Baird thought it important to understand every aspect of the subject matter before starting to draw or paint. Drawing was important in the other Scottish colleges (see MacBryde and Colquhoun’s late 1930s work), but the levels of concentration that enabled Hennessy’s friend and fellow student, Alexander Allan to produce Bird Cage in 1938 were a level beyond what was going on elsewhere.

Alexander Allan, Bird In Cage, ink on paper, 38 x 37cm, 1938, University of Dundee Fine Art Collections

Patrick had established himself as one of the UK’s leading etchers, and then created a unique identity for himself with his panoramic abstract visions of East of Scotland rural life. His realities trumped photographs with their expansive vistas and clearly articulated information both in foreground and well into the distance. Patrick never used photography. His car and sketchbooks were his most important tools. He worked in a studio with no window, just a skylight, and his visions were amalgams of sketches made on his many trips, driving around the countryside. His paintings were constructs of different realities made into a fantasy of endless idyllic landscapes. He was not catching a moment in time, a fleeting impression, a strange perspective. He was organising a reality that fitted the shape of his frame and capturing, in crystal clarity, a rural life that city dwellers wished were true.

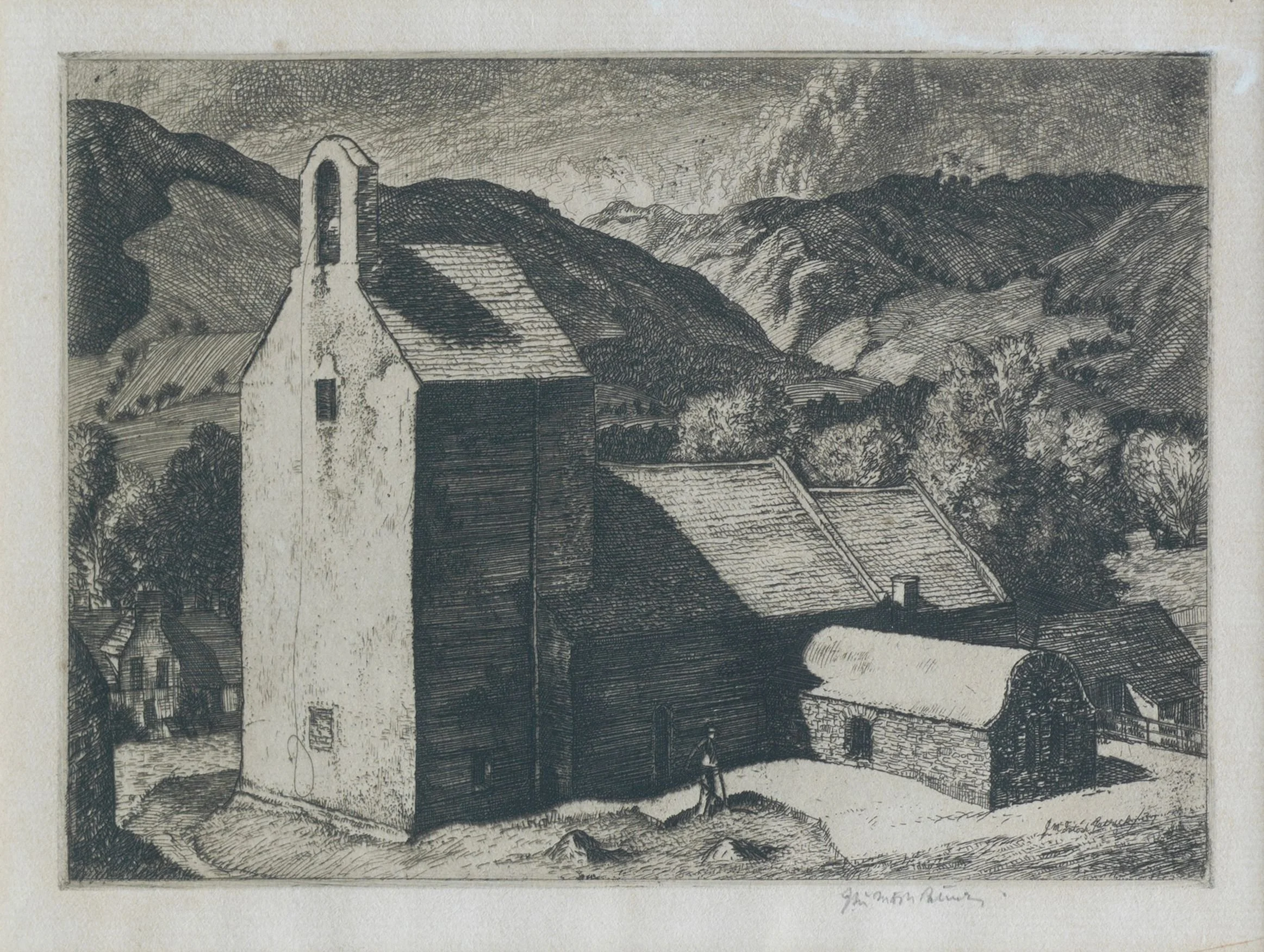

James McIntosh Patrick, Stobo Kirk, etching, 10 x 14.5cm, 1937, private collection

Baird’s super-realism could extend into surrealism, and he arrived there possibly earlier than anyone else in Scotland. His painting of his long time girlfriend, Anne Fairweather, nude on the beach at Montrose, The Birth Of Venus, in 1934 may have been influenced by Edward Wadsworth, but perhaps just as much by Botticelli or Cowie; perhaps he’d seen surrealist work in Rome in 1939, but maybe he just arrived at the same place through the same technique as Patrick, amalgamating his various sketched realities into a super-reality, organised to make still a fantasy.

Edward Baird, The Birth of Venus, oil on canvas, 51 x 69cm, 1934, National Galleries of Scotland

When students at Dundee College of Art read or heard about the extraordinary events at the International Surrealist Exhibition in 1936 ( Dali nearly suffocated as he lectured from inside a diving suit!), they could see that the British paintings on display were perhaps overshadowed by Baird’s work. They would definitely have a sense that their teaching staff were in-the-moment.

In addition to Hennessy and Vannet, the three years when Patrick and Baird were at Dundee College together saw other students like Alexander Allan and Harry Craig develop techniques that would underpin future artistic careers. Allan was an early friend of Hennessy’s in the same year at College, whilst Craig, in the same year as Vannet, was Hennessy’s boyfriend, and his entire life was to be entwined with Hennessy, in parallel with the two Roberts, although he and Hennessy never fell on hard times. The two Roberts met Hennessy (and presumably Craig) in Arbroath in the summer of 1938 and formed a long term friendship.

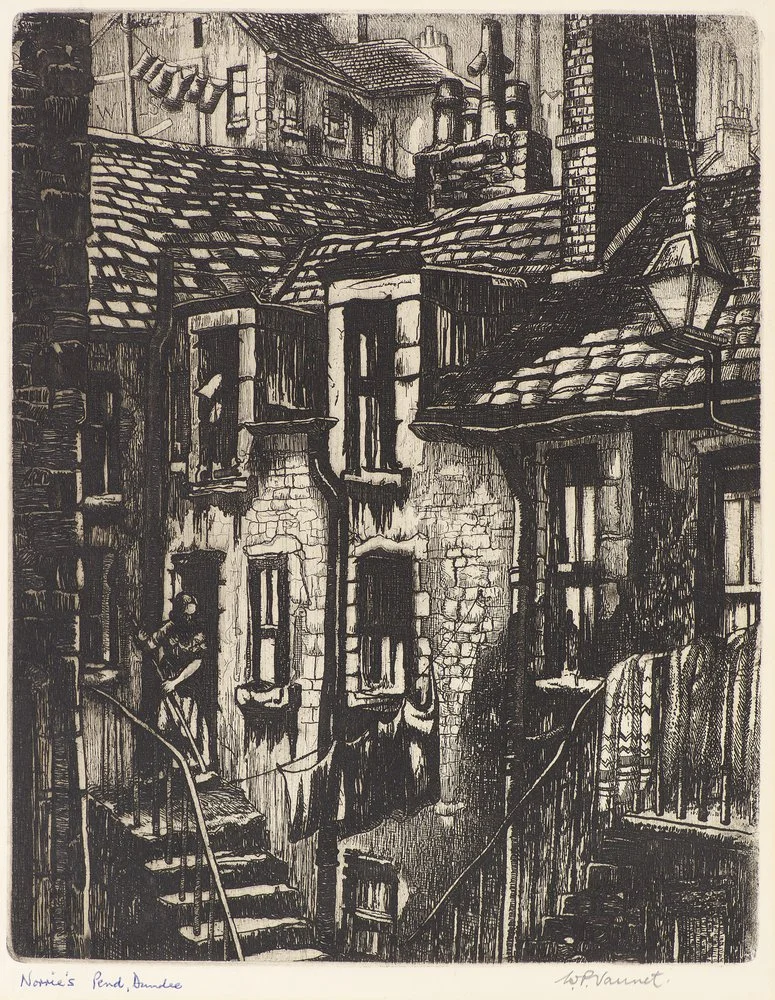

The July 1938 press reports may have been mistaken on the print front, because Vannet was not known for woodcuts, but by 1938 had developed a remarkable facility at etching. There are at least seven etchings signed and dated by Vannet from 1937 and 1938. Inspired by Patrick, and through him, the rich recent work of artists like F.L.Griggs and Muirhead Bone, Vannet produced top quality etchings of scenes in Arbroath and Dundee that year. They are highly detailed and must have required considerable investment of time. Surely they were produced for Vannet’s first public exhibition.

Vannet loved Arbroath. Hennessy hated it. Vannet’s subject matter was the harbour, fishing boats, roofs, pends. He also liked architectural angles, with light and shadow playing across walls and roofs. He liked commotion. Hennessy wanted to hold his images in an airless, deathless stasis. He wanted controlled environments. He liked painting stilled people, including himself, in a healthy and vigorous pose, as though caught by a photograph. Vannet rarely ventured into this territory. His landscaped people were remarkably similar to Patrick’s and to those of another Patrick-influenced Carnoustie painter, James Torrington Bell: stick insects and shadows that were almost incidental representations in the sweep of the eye across the picture. However, there is a striking oil painting attributed to him, The Carver, signed W.P.V. and dated 1953, that demolishes any idea that he couldn’t paint people.

Patrick Hennessy, Self-Portrait, oil on board on gesso, 46 x 37cm, 1938, private collection

1212Hennessy’s 1938 self-portrait tells us he was a confident young man, keen to present himself. It was either youthful bravado or a powerful element of vanity that made him submit this painting in his first ever RSA bid the following year. His upturned collar is a key indicator of difference. His maturity is confirmed by his moustache and his strong facial features - temple, cheekbones, chin, lips - are all accentuated by healthy flesh tones. His eyes are dark and fathomless, suggesting mystery. He looks a travelled sophisticate, not a boy from Arbroath, who had grown up and was still living in a flat with five siblings above a shop just off the West Port.

He knew he was good. His painting touch was light and sensitive, following Patrick and Baird in eschewing the signs of the brush. It’s a polished performance of timeless quality. A mile up the road at Cairnie, 330 years before, William Aikman would have been delighted with the same result. A little too casual for his customers, perhaps, but with its mix of realism and romance, a calling card to be set fair for a handsome career as a portrait painter.

If we compare Hennessy’s 1938 Self-Portrait with his 1936 Portrait of the Artist, we can see the influence of Patrick and Baird on his work. The finesse, the conviction to effect reality, the fine brushed modulations of tone and colour were not in his toolbox in ’36. Emotion and bravado are to the fore. The ’36 oil could only have been painted in that moment, it’s sense of fashionable movement and dash, and it’s rather clumsy interface between jumper and bare floorboards racing backwards to what might be a floodlit glass door, speak of a youthful rush and a wish to join an art world that contained the Bloomsbury set, Stanley Spencer and Wyndham Lewis.

Look at the length of his collars, upturned, and shooting off signals to the big wide world out there! There’s pride and perhaps defiance, but chief amongst the messages is “I’m An Artist!!” Later in his artistic career, he painted pictures of boys and young men in which he portrays the central character standing or sitting apart from his peers, creating a feeling of isolation and difference. With his portrait, here he was at 19, telling himself that he was going to be special. He was going to be accepted into the world of leading artists.

Patrick Hennessy, Portrait of the Artist, oil on canvas, 53 x 36cm, 1936

Baird appears to have had no such vanity. His motivation was hard-work and learning. He painted portraits, but often didn’t finish them. He knew that with more capability he would be able to improve them in the future. In 1938 he was working on a portrait of his friend, Dan Crosse. He sent it to the RSA in 1942 with a NFS tag on it. This is a painting that Baird’s wife, Ann, still had stored in her house in 1972, when she died. Its hard to know which, if any, sections of it, Baird would have regarded as ‘finished’, but one might assume that the face is completely worked up.

Edward Baird, Dan Crosse, oil on board, 32 x 25.5cm, private collection on long term loan to National Galleries of Scotland

The smoothness of the skin painting is notable, and the fineness with which Baird worked on eyelids, lips, forehead and nose underline his concentration levels and his interest in, and ability to record, accurate detail. The skin tone is swarthy, and Dan, like the youthful Hennessy, exudes health and vigour. Baird didn’t cut corners. Fully understanding a subject, and documenting it’s visual aspects, were central to Baird’s opus moderandi.

This portrait is one of Baird’s most relaxed, and presumably not a commission. But compare it with Ian Fleming’s 1938 Two Roberts, also a labour of love - and an artistic challenge - and the conceptions are very different. Fleming finds likenesses through powerful observation and draughtsmanship, but then uses thicker brushes and dabs of colour, leaving the detail for the viewer to fill in. For Baird, the famously slow worker, this may have seemed lazy and lacking in craft. However, his sketch, despite it taking a lot of time - and perhaps a lot of Crosse’s time, too - was never offered for sale.

Hennessy would have noted this. And whilst he clearly absorbed and valued Baird’s methods, he painted more quickly and wanted to sell. Like Aikman, he had an instinct, a confidence, and a talent to seek out connections that would help him and turn them into opportunities.

Kevin Rutledge, in his illuminating biography, wonders how Hennessy could have achieved a one-man show at a Dublin gallery in 1939, three months after he moved to a city where he had no established history, at the tender age of 23. (Note 5) He postulates that Hennessy would have seen the opportunity at the 1938 Empire Exhibition in Glasgow to introduce himself to the widest possible range of art contacts. Running from May to December, the Exhibition at Bellahouston Park attracted nearly 13 million people (over 60,000 people per day) and included a Palace of Arts, where Rutledge speculates that Hennessy, with his Irish heritage, seized an opportunity to meet (and charm) Mainie Jellett (1897-1944), “the only serious exponent in this country of the ultra-modernist school of painting.”(Irish Times, 1927), who painted two large murals for the Irish pavilion. It was she who opened Hennessy’s 1939 exhibition and opened doors for him to establish himself in Ireland.

Before we leave Jellett, it’s instructive to note her ideas, here expressed in her essay “An Approach to Painting”: “The idea of an artist being a special person, an exotic flower set apart from other people is one of the errors resulting from the industrial revolution, and the fact of artists being pushed out of their lawful position in the life and society of the present day. … Their present enforced isolation from the majority is a very serious situation and I believe it is one of the many causes which has resulted in the present chaos we live in. The art of a nation is one of the ultimate facts by which its spiritual health is judged and appraised by posterity.” (Note 6)

I quote her words because this way of thinking would have chimed strongly with Edward Baird, nationalist, socialist, who would have also wished to see his art as work.

Just like Aikman, Hennessy was to be gone from Arbroath all too quickly, and to a very successful art career, starting with portraits, but we’ll come on to that later. In July 1938, he had probably met the two Roberts, and he had met Harry Craig, and his sexuality must have been set. The future seemed more positive. Identifying as an artist, a Catholic, a homosexual, and ambitious had not been an easy fit with working class Arbroath in 1938.

Vannet was a different character in some respects: studious, careful, presbyterian, conservative; but in others he and Hennessy had commonality: they were both industrious and clearly determined to succeed in their careers. I’m not clear what Vannet’s intentions were, and perhaps we’ll never know, because the war changed everything for him. By the time he came back into civilian life, in 1946, aged 29, he was beyond the moment for risking all on making a living as a professional artist. He had an MBE and six years of navy experience, including management and teaching.

At the 1938 exhibition, the reports, as mentioned before, said that Vannet produced still lives (a specially good one being of nautical objects), portrait studies, and water colours. I haven’t been able to track any of these down, in fact, I can’t find any note of them being exhibited or sold. In 1939, Vannet had two pictures accepted at the RSA, both etchings; and we have records of at least two etchings that were produced by 1937, five more by 1938, and a further three by 1939.

W.P.Vannet, Girl Mary, etching

Girl Mary was one of his 1938 productions, a relatively simple concept: a fishing boat, pier, the shadow of a man, gulls; with long vistas of water and distant shores in the distance. The fishing boat, Girl Mary, registered in Arbroath (AH37), was three years old in 1938, and would only have a short life because having been requisitioned by the navy and turned into a patrol boat, it was sunk in enemy action in the Firth of Forth in 1940. Here it is, in relatively pristine condition with Vannet tackling its masts, spars, sails, superstructure, ropes, and nets in full detail, and adding clear sky and shadows to his technical challenge.

Its a technical drawing exercise that underlines the skillsets that were central to the Art College’s ethos at the time. The complex etching of multiple overlapping angles, the care required to work out how sunlight and shadow would play on each surface, speaks of a craftsman whose mission is to make something that creates an effect of ease through painstaking planning and execution.

Just like Patrick, the youthful Vannet saw the world as it might ideally be seen. If there were any inconvenient realities, they were overlooked or replaced by elements that fitted harmoniously. The Empire Exhibition was being held in Glasgow that summer. It was unusually wet, but Scotland was glowing, modernity and excitement in urban centres combined with rural harmony and natural beauty: the ‘glass half full’ approach was winning hearts and minds.

Patrick’s penchant for rural idylls led to his leanings towards Griggs. Neither had much fascination for sea, docks and harbours. Vannet whose preferences were for more noise, angles and action surely drew more from Bone, whose etchings of construction sites, scaffolding, dry docks, and shipbuilding were widely know through editions and publications. However, there was one aspect of Griggs’ work that the young Vannet absorbed: the capturing of sunlight on a monochrome print. Girl Mary illustrates this well.

Technical skills were at the core of the curriculum at Dundee College, where observation and accurate drawing were still linked to many trades - from medical to engineering and building, but in Dundee to print as well. The same principles held for Arbroath, where Alan Inglis ran an art department that aimed to educate draughtsmen in all kinds of industries, with creative work only one element of the output.

And Arbroath had a small but lively printing industry. Two broadsheets, The Arbroath Herald and The Arbroath Guide were printed weekly, with the Herald’s publisher also producing periodicals like the Book of the Braemar Gathering, and publishing books and booklets. Vannet had been in their studio producing the illustrative art work on the headings of the articles in The Braemar Royal Gathering Book since he was 18.

W.P. Vannet, Illustration for The Scottish Annual & Braemar Gathering Book, 1946

In 1938, McIntosh Patrick had a painting of Traquair House up on his easel. His focus had moved from etchings to rural fantasies to realism that didn’t require so much imagination. His various views of Stobo Kirk that he turned into pictures between 1936 and 1940, from different angles and in different seasons; and his various etching states of the same subject, in which new features appear, show his deep interest and empathy with architectural subjects.

If these pictures had fabricated elements they were minor adjustments made to embellish the effect. He wanted to document. He loved detailed drawing, and his architectural capabilities had been in place for nearly twenty years, going back to his school-days working in Charles Soutar’s office. Soutar took a great interest in Charles Rennie Mackintosh and there are accounts of his office containing several Mackintosh pieces.

Patrick’s Traquair House is a tour de force of architectural drawing, with light from high on the left behind the painter (and viewer) flooding and shading a huge range of architectural features: flat and curved expanses of slates, gable-ends, chimneys, dormer windows, and roofs in all angles. The evergreen foliage glistens Baird-like, whilst the intense wintry light clarifies the lines of deciduous tree-forms. In the distance the contours of hills and their cloud-shadowed patterns are picked out with high definition.

Patrick’s constant shifting from black and white etching to colour oil painting and back was often helped by him presenting his subjects in wintry conditions, but in Stobo and Traquair we see sunned and shaded grassy slopes, green and yellow and orange.

James McIntosh Patrick, Traquair House, oil on canvas, 35.5 x 45.5cm, 1938, National Galleries of Scotland

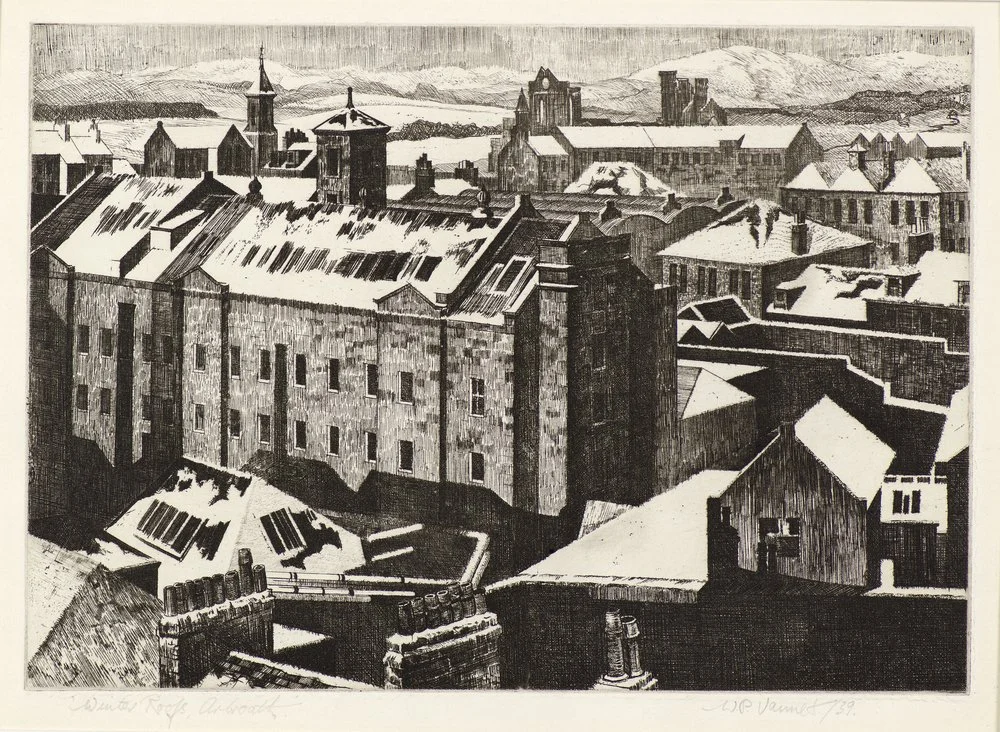

Vannet would be aware of Patrick’s winter contrasts when he was producing Winter Roofs, Arbroath in early 1939 - one of his RSA submissions that year. His high vantage gave him a challenge as he looked north west over the mills, factories and warehouses of his industrial town, past the ruined Abbey with the famous Round O, with the Angus Glens brought closer, for stronger framing, in a move Patrick would have recognised.

His vista covered multi-directional roofs, walls and windows in bright low sunshine and dark shade, with snow cover holding on some roofs and melting on others. There are so many architectural angles, so many shadows (including those from off-stage chimneys to the left) that the young man must have realised he could not possibly manage the fine detail without spending Baird-times on the plate.

Consequently, windows have no astragals; stonework in full sun that Patrick would have picked out with pointing in tact, Vannet effects through various intensities of shading and stippling. His foreground bricks and mortar, individual roof slates and chimney pots are the only elements of the picture striving for fine detail and that only accentuates the rather sloppy hatching of a gable/roof in the bottom left of the print. Patrick would have taken on less and offered more definition. Notwithstanding that, the shaded walls in his Stobo Kirk etchings could have offered more than cross hatching. Baird would have noticed that.

However, the overall effect of Vannet’s roofs is a sweeping panorama that matches Patrick’s early etchings and rural paintings for scale and immediate impact, but lacks Patrick’s subtlety, intensity and his contrived navigational pathways: the ones that signpost the viewer into and through the scene. Vannet was less of a formal planner and more of a documenter. And he hadn’t learned at this stage the scale he could manage.

W.P.Vannet, Winter Roofs, Arbroath, etching, 15 x 21.5cm, 1939

Hennessy had won a travelling scholarship from Dundee Art College alongside his post-diploma scholarship and he spent some of the winter of 1938/39 meeting up and travelling with his new friends, Colquhoun and MacBryde, on their trip to Paris, Avignon, Rome and Florence. Charles Pulsford and William Gear reportedly met up with the Roberts in Paris, and quite possibly Hennessy was there too.

They were all away when the Exhibition of Scottish Art, the biggest ever mounted to that point, surprised and astonished critics and audiences at the Royal Academy in January 1939. Presumably this was part of Westminster’s Scottish amelioration offensive. And perhaps it wasn’t really necessary because the nationalist impetus had dissipated somewhat in the late 30s, especially in the cultural sector. McDiarmid had moved from Montrose to Shetland in 1933, ‘The Modern Scot’ journal, the intellectual flagship of cultural nationalism, had ceased to exist, although not before James Whyte, its proprietor, had presented a “Modern Scottish Art” exhibition of some substance in St Andrews in 1935. Hunter, Peploe, Fergusson, Bliss, Cowie, Baird, Gillies, McTaggart and Patrick were all represented. Whyte’s boy friend, John Tonge, produced a new survey of Scottish Art: “The Arts Of Scotland” in 1938.

The Two Roberts went to Venice and to Belgium and Holland too, returning in May 1939, but it seems that Hennessy came back a little earlier. Perhaps he would have come back In April to see himself represented on the walls of the RSA by his Self Portrait (presumably the 1938 one - see above) and a Still Life. Aged 23, he was exhibiting alongside Vannet (Winter Roofs and The Old Boat, Auchmithie) and his teachers, McIntosh Patrick and Baird; and Cowie was also represented amongst many others, including Alexander Allan.

Hennessy had applied to Arbroath Council to fund him to attend Hospitalfield from June 1939, and extraordinarily, perhaps due to the same group of people who were responsible for the July 1938 exhibition, they agreed to do it.

One wonders about his motivation, because he must have already been planning to take his leave from Scotland and move to Ireland. Perhaps the opportunity for him to have a summer of independent living without financial pressure, and with the opportunities that he’d seen Colquhoun and MacBryde enjoying in 1938 was seductive. His later claim was that he hated it, and James Cowie thought his presence there was disastrous, but the evidence of his future work is that a few months with Cowie could have been a greater influence than he would be ready to admit.

Patrick Hennessy, The Lakes of Killarney, oil on canvas on board, 46 x 35.5cm, no date, private collection

Cowie, in his report on the year’s activities, bemoaned Hennessy’s attitude and his presumption that he could invite all and sundry to join him at Hospitalfield. One wonders whether Hennessy used the opportunity to challenge Cowie’s authority on a number of fronts, artistic ones being less of an issue than Cowie’s management style and personality and perhaps even more so, Hennessy’s gay lifestyle. He was perhaps more able to express this openly in Scotland than he had ever done before, and perhaps he didn’t feel it was going to be a hindrance because he was going to leave the country for good shortly. Cowie and his wife were responsible for all aspects of student life at Hospitalfield and accepting (illegal) homosexual activity would have jeopardised their roles and jobs. This is conjecture, of course, but Cowie is not explicit in his report of Hennessy’s misdemeanours, and I am reading between the lines.

The persuasiveness of Cowie’s artistic approach was strongly felt by other artists in residence that year, notably Alexander Allan and Charles Pulsford. Allan was already clearly under Baird’s spell, but both he and Pulsford produced Cowie-inspired work that they would not repeat.

Alexander Allan, Fantastic Landscape, oil on board, 34 x 45cm, 1938/39, (copyright of the artist’s estate), Dundee Art Galleries and Museum Collection

Patrick Hennessy, Liv Hempel, pastel on paper, 47 x 33cm, 1939, private collection

David Evans, September Sunday, Oil On Canvas, 122 x 112cm, 1973, private collection

Charles Pulsford, Untitled(Surrealist Townscape), oil on plywood, 68 x 105cm, 1939, ( copyright of the artist’s estate), National Galleries of Scotland

Vannet completed his diploma in June 1939 and followed the same steps as Hennessy in getting a maintenance grant for post-graduate study. There were limited options for the future. The Foreign Office was already advising against travel to parts of Europe and Scots were arriving back home sensing the upcoming war. J.D.Fergusson and Margaret Morris had packed up studio and school and would be back in Britain within the next few weeks. Vannet completed his post-graduate study, won a travelling grant ( £125, compared with Hennessy’s £60) and enrolled in the Navy.

Hennessy departed Hospitalfield mid-session and was in Dublin by September 1939. Whilst Vannet committed his life to the war effort, winning an MBE for his work on improving submarine gunnery, Hennessy used the next seven years to establish a substantive reputation as a major Irish artist. He leaned on his birthplace in Cork for his Irish identity and hardly mentioned Scotland at all. He worked on portraits to make a living, he sold still-lives, and then gradually established his own style: a blend of hyper-realism, mild surrealism, and imaginative constructs. He was regarded by Irish critics as brilliant but strange, and coming from outside the Irish tradition.

They were right, he came from the heart of a strong Scottish movement that had reached its zenith at that late 30s moment: for a Scot, it’s almost impossible to look at many of Hennessy’s paintings without seeing their roots, sometimes almost straight lifts from Baird and Cowie. His disciplined approach to observation, draughtsmanship, and business acumen were perhaps founded on Patrick’s steely determination. Scots will also see parallels with the realists from Arbroath and Montrose who followed, notably John Gardiner Crawford and Rodger Insh, but perhaps even more so, in the eerie realism of David Evans.

McIntosh Patrick, always generous, throught both Vannet and Hennessy were special. Speaking of Vannet, in 1946, he said “his work as an etcher is quite outstanding with a sense of design and a graphic quality which shows unusual ability.” And Kevin Rutledge quotes Patrick remembering Hennessy when he was in his 80s: “I recall him as a very brilliant student with a great deal of facility, able to produce rather highly finished canvasses very quickly and with a great deal of inventiveness. Even though it was fifty years ago, I can recall him only because he was outstanding.”

W.P. Vannet, Norrie’s Pend, Dundee, also known as Old Dundee, etching, dimensions unknown, c.1946

James McIntosh Patrick, Old Town, pencil on paper, 17 x 12cm, no date.

In 1946, Vannet, demobbed, was re-entering civilian life with an ambition to underpin his art practice by training to be a teacher. He was the first secretary of the newly formed Arbroath Art Society, and set up a substantive educational and talks programme. On 7th June that year, Edward Baird gave a talk for the Society on “The Art of Seeing” (with James Torrington Bell in the chair)

That Autumn, having welcomed Harry Craig to a life co-habiting in Ireland, Hennessy and Craig were hosting a visit by Colquhoun and MacBryde that produced very important work, especially by Colquhoun. Baird, who had married the year before, only had three more years to live, all with poor health. Cowie, moved to Edinburgh a year later, with Ian Fleming taking his Hospitalfield role from 1948.

Vannet would go on to regard McIntosh Patrick as a friend, and he would have many dealings with Cowie before Cowie left for Edinburgh. Hennessy seemed to wash his hands of everybody and every institution in Scotland, with the exceptions of his friends, Alexander Allan, and Harry Keay; and Baird.

I’m indebted to Kevin Rutledge again to quote from Hennessy’s correspondence with Harry Craig: “I never look back at that dreadful College, God forbid, and I never want to hear of Dundee again, of Principal Cooper, Cowie, Mr. Day, Bannockburn and – I ran out of breath here”. And later: “On the rare occasions that you mention the names of the people who graduated with us, I have the greatest difficulty in trying to remember who they were, and at the same time a sense of dim horror that I should be tempted to look back down the unhappy perspective of my life in Scotland.” And thanks to Kevin Rutledge again, for an ability to quote from Hennessy writing to Alexander Allan in 1946: “Give my regards to Baird and my congratulations on his marriage. My friends McBryde and Colquhoun are full of an aesthetic-cum-revenanting zeal for the best interests of Scotland which rather saddened me.”

There’s a sense of Hennessy burning bridges so that no-one in his new life would make the connections that seem obvious now. Vannet was always ready to pay respects to Patrick’s influence on his work, and, after a short dalliance with abstraction with J.D.Fergusson’s New Scottish Group around 1950, he followed Patrick to a looser style, in a career which I hope I can cover in a future article. Hennessy was a product of the Patrick-Baird-Cowie axis, and we might like to start to identify him within the Scottish art pantheon, recognising Irish art’s complementary claims.

James Cowie, Portrait of a Child, oil on canvas, 102 x 69cm, 1939 (completed 1950), Dundee Art Galleries and Museums Collection

Patrick Hennessy, Atlas Beach, oil on canvas, 63.5 x 89cm, no date, private collection

Rodger Insh, Sara Eating Crisps, Ferryden, dimensions unknown, gouache on board, 1990, private collection

If there is a footnote to this piece it is that the circumstances in which art flourishes can be the result of year’s of nurturing. That July morning, I hope J.T.Ewen took some pride from his work. Rather like Balzac’s Country Doctor, Ewen’s engineering of a world in which young artists could be supported by the skills and resources of people like Inglis, Cowie, Patrick and Baird and the institutions they worked for, established a seedbed that would make Arbroath an important art centre for many years to come. I’ve called Vannet and Hennessy the ‘Patrick-Baird boys’, but they were all indebted to J.T Ewen.

Roger Spence

Footnotes

Note 1: James McGregor, architect, had recently been elected convenor of the art sub-committee of the Library, and J.T.Ewen acknowledged his role in making things happen.

Note 2: See Patrick Elliott, Edward Baird 1904-1949, (Scottish Masters 17), published by the National Galleries of Scotland, 1992

Note 3: See Roger Billcliffe, James McIntosh Patrick, published by the Fine Art Society for the City of Dundee District Council, 1987

Note 4: See Jonathan Blackwood, Portrait of a Young Scotsman, A Life of Edward Baird, 1904-1949, published by the Fleming-Wyfold Art Foundation, 2004

Note 5: See Kevin Rutledge’s biography of Patrick Hennessy at http://www.modernirishmasters.com/

Note 6: Rutledge, ibid.