Donald Bain: Artiste Peintre

For the self-taught painter Donald Bain, the voyage through art was a bumpy one. But in the best of his work, he stands up as an artist of remarkable originality. Although his legacy is bound up with the life and work of his mentor, J.D. Fergusson, Bain was a truly independent force. A proud Scot, he revelled in the Celtic connection which drew him into a dialogue with the art of France.

Donald Bain (1904-79) remains a difficult character to place in Scottish art. The self-taught Glasgow painter was an independent force who made his presence in the Scottish art landscape known with his full-bodied, high-key paintings. Vehement in his insistence that artists must be independent, he was fiercely committed to his own principles and scathing towards those establishment “sooks” whose run-of-the-mill work displeased him [1]. For all of his enduring association with the legacy of his mentor J.D. Fergusson and the New Scottish Group of the 1940s, Bain stands alone as the irrepressible creator of an arresting, exciting and often beautiful body of work.

Bain’s oeuvre - comprising still lifes, landscapes, street and city scenes, figure groups and Celtic fantasies – is almost as variable in its quality as in its subject matter. Writer, curator and dealer William Hardie, who saw something very special in Bain, noted that his work at its best is adventurous, animated and unambiguous [2]. But Clare Henry reminds us that Bain’s output was “as uneven as his temper” [3]. When the Glasgow Print Studio mounted his memorial exhibition in 1980, their catalogue towed a tactful line: “it is not for us to declare at this stage whether Donald Bain will be remembered as one of the finest Scottish artists of this century, but he is certainly one of the most durable” [4].

Bain is nothing if not a “durable” artist. His paintings endure in the mind for their vigorous handling, strength of colour and raw, robust beauty: in this, they are very distinct indeed. The story of Bain’s life, too, is a memorable one: “never a dull moment”, it has been said [5]. Bain was born in Kilmacolm, moved to England with family, worked in industry and only took up painting seriously on his return to Glasgow during the Second World War, aged 36. He dove headlong into the continental art scene in the immediate postwar years and despite frequent ill health as well as a home and a family in Springburn, Glasgow, he made long working visits to France until shortly before his death in 1977, aged 73 [6]. He won prizes and medals [7]. He showed work in the Columbe d’Or during spells in the Côte d'Azur [8]. He met Picasso, Matisse, Christian Dior and Frank Sinatra [9]. Although today he occupies a place on the margins of the accepted Scottish art narrative, Bain’s name is a “durable” one for the relationship he nurtured with the continent throughout his artistic life; in Donald Bain’s work, Scotland and France are bound together in an intriguing and exciting fusion.

Bain’s work might have been uneven, and he may have figured as a rather eccentric presence in the Scottish art scene - “he lived in Springburn but he always wore a French beret” - but he was no mere poser [10]. In the strength of his painting, always genuine in its integrity and sometimes brilliant in its quality, Bain deserves every bit of the praise his most committed supporters, from Fergusson to Hardie, have conferred on him. This article traces a thread of Bain’s development and offers a flavour of his painting, showing his talent as the creator of a vibrant and individual body of work; for all of Bain’s originality, it also considers the influence of Fergusson and the integral role of France. In doing so, it builds a portrait of the independent-spirited “artiste peintre” – to use the phrase Bain loved – who looked to France for a Celtic connection [11].

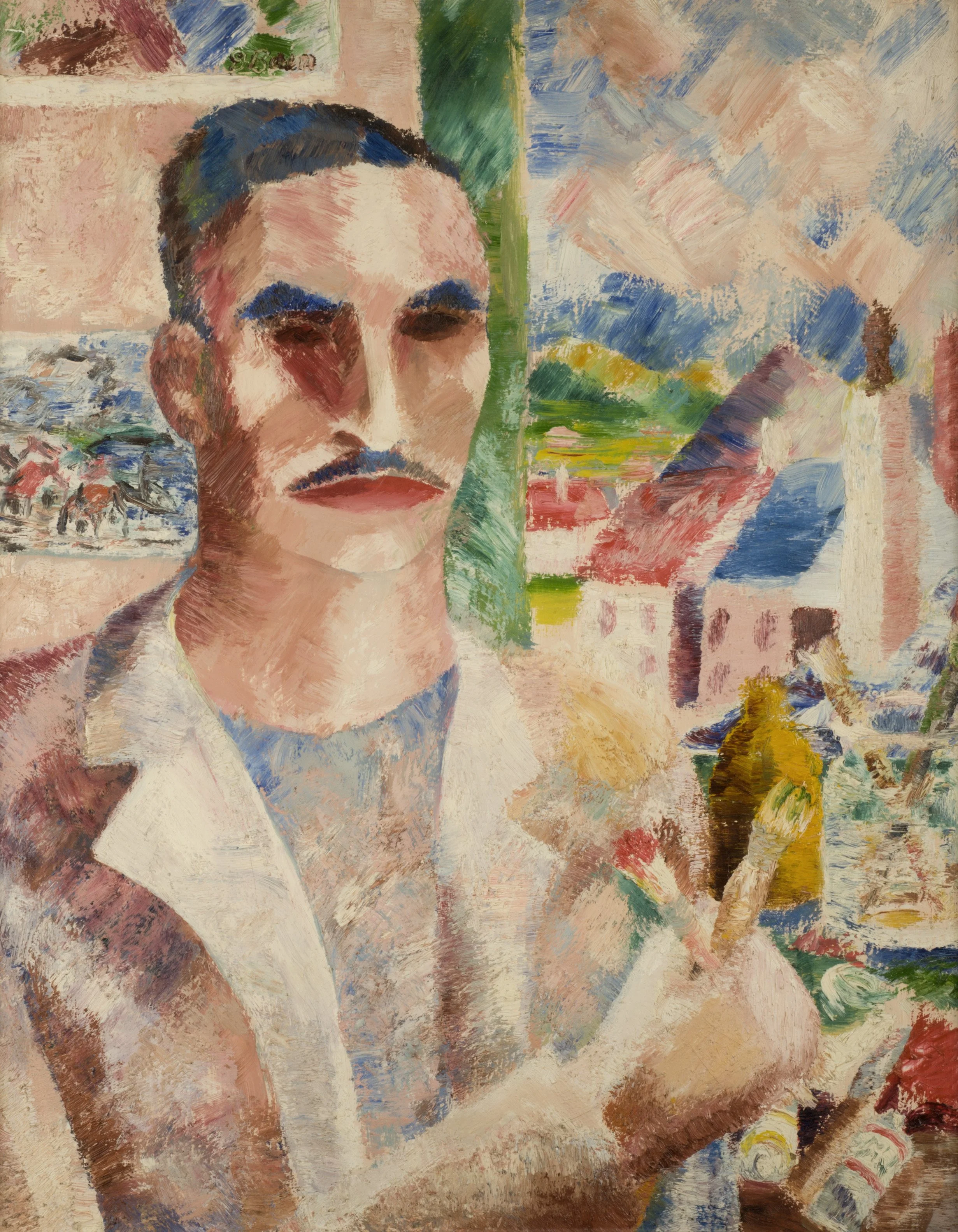

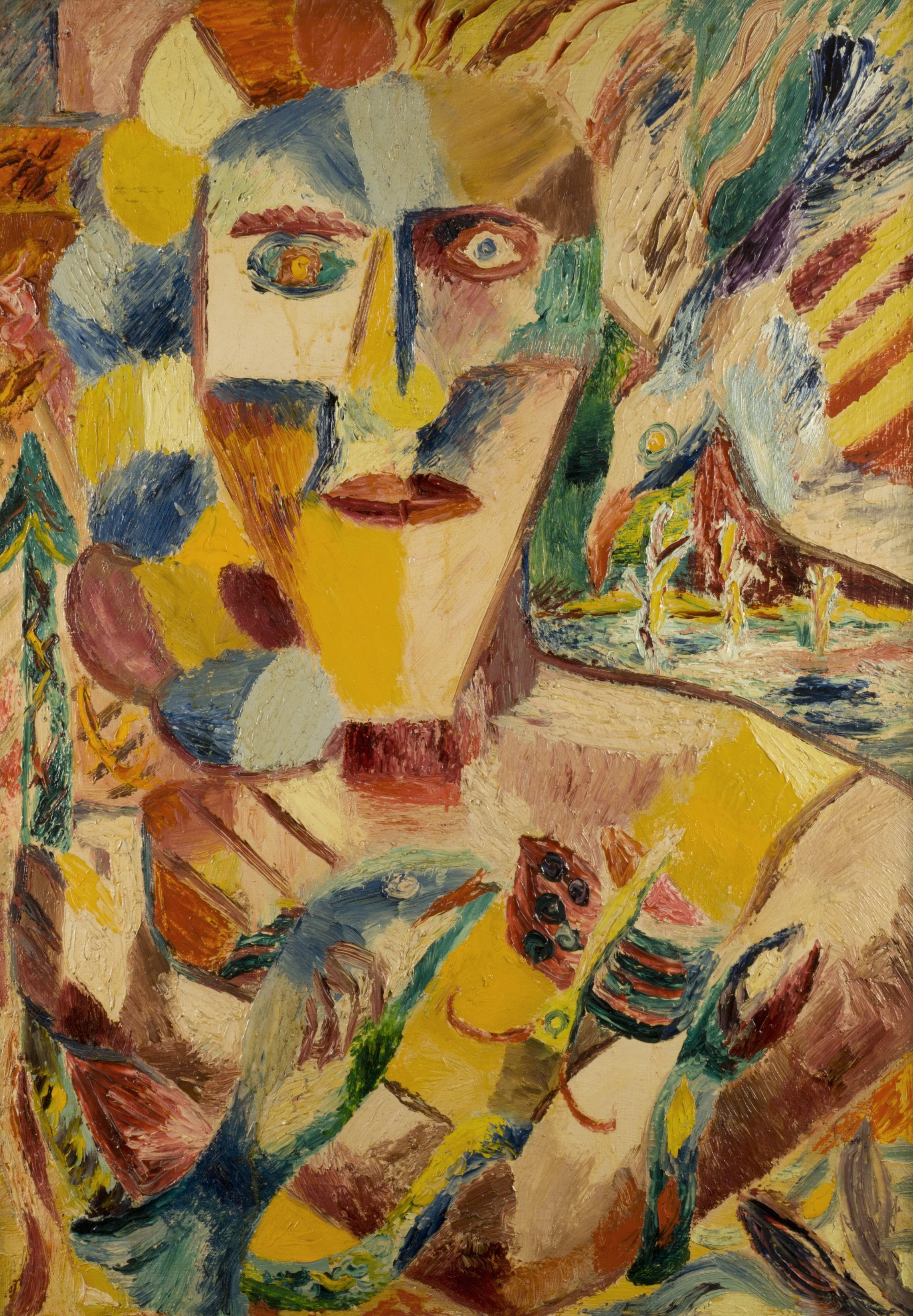

Donald Bain. Painter’s Portrait. Oil on canvas. 76 x 62 cm. 1946. Courtesy of Perth Art Gallery (Culture Perth and Kinross Museums and Galleries).

Donald Bain’s place in Scottish art has been determined in large part due to his proximity to J.D. Fergusson. He is often discussed in Fergusson’s shadow. This is understandable, particularly given Fergusson’s greatness, even if it is rather ironic: Bain was a singular force, but he was also Fergusson’s great protégé [12]. Bain’s painting developed rapidly after his move to Glasgow in 1940, around the time of his first meeting with Fergusson. The elder Fergusson was a self-taught artist who had won great acclaim in France; he had also settled in the city during the War. As the instigator of the New Scottish Group, which celebrated Modernist self-expression in art and letters, Fergusson provided Bain with the confidence to develop his painting from its bare bones along progressive, anti-academic lines [13]. With no formal training and limited means, Bain applied himself to the task with seriousness between shifts in Glasgow’s shipyards. His strenuous efforts resulted in a body of work which stands up as strikingly – indeed, forcefully – individual. At certain moments, Bain’s palette shows the influence of Fergusson, but his proud independence is plainly evident across the breadth of his work. It was after all Bain’s originality, his opposition to the Scottish art establishment, which Fergusson most admired; he encouraged Bain to protect this essence [14].

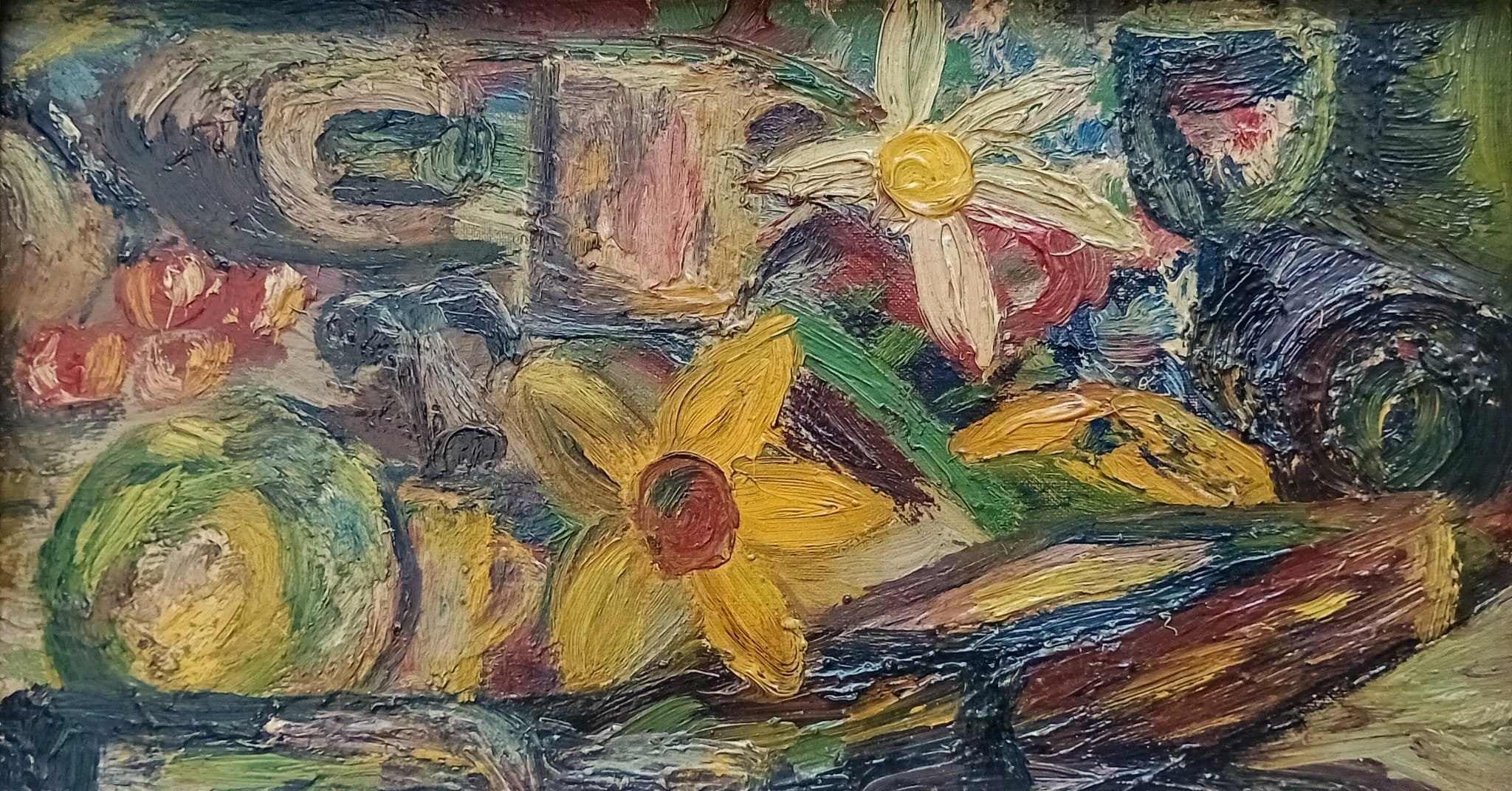

Bain’s 1943 Still Life with Mallet shows his early confidence as an intuitive, gestural painter. It is an imagined amalgam of still life objects – flowers, mugs, tools, fruits – squashed into a modestly-sized picture plane. Bain has set his sights on a traditional subject but he has broken all the rules of composition and perspective. There appears to be no evidence that the work is underpinned by a solid piece of drawing, and without this framework to ground the picture, Bain has applied himself to a bold, gutsy exploration of painterly texture. He lets loose on the canvas. On the left, he has summoned a handful of cherry tomatoes with only a few loose licks of the brush; on the right, in stark contrast, is the heavily built-up base of an overturned bottle, dark and sticky with pigment. The overall result of his excitement is more than slightly clumsy, but Bain’s enthusiasm is infectious. His command of the medium suggests a creative force to be reckoned with; his rule-breaking treatment of a traditional subject foreshadows his artistic life as a devout, even reckless, nonconformist.

Donald Bain. Still Life with Mallet (Yellow Flowers). Oil on canvas. 44 x 23.5cm. 1943. Private collection.

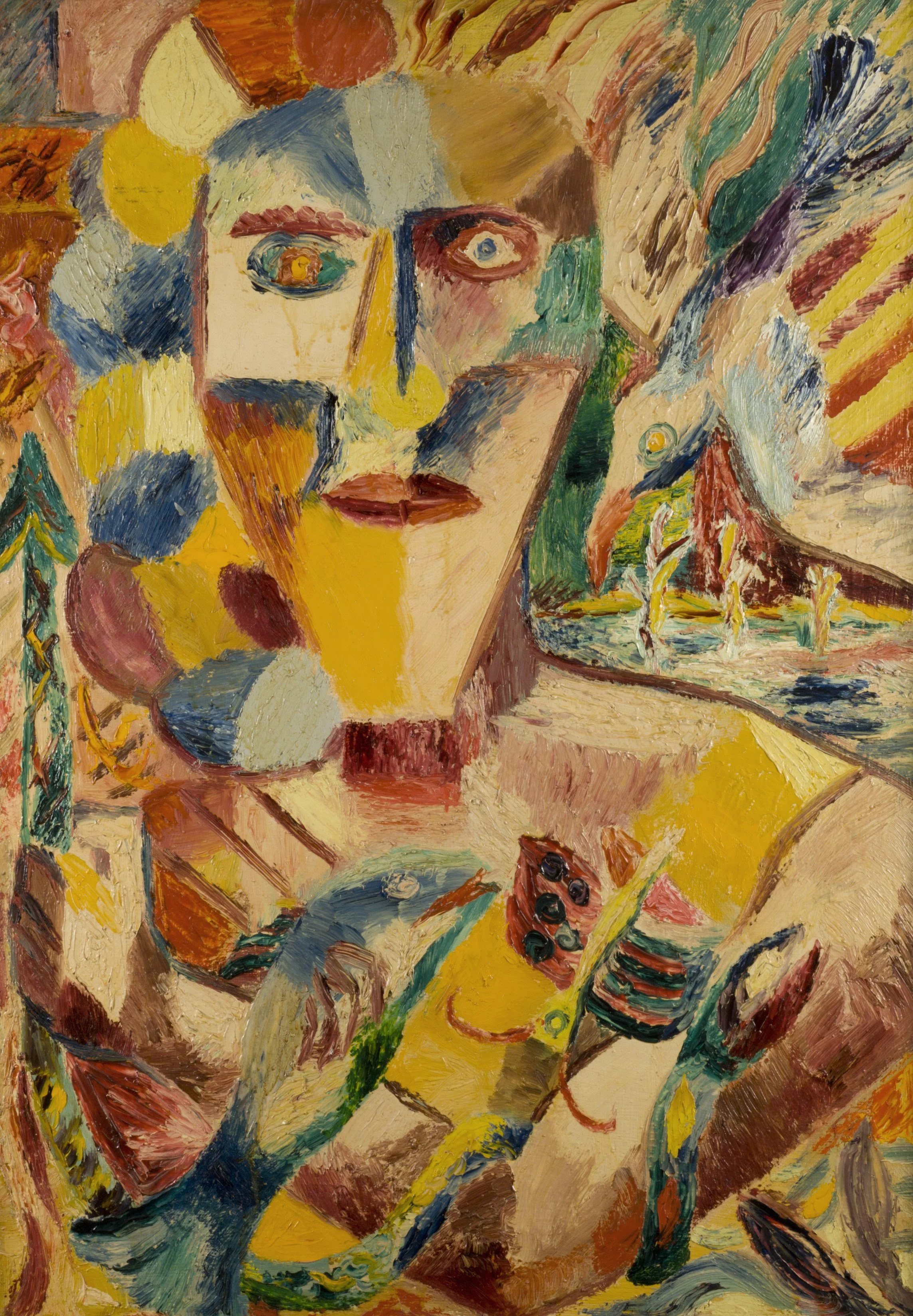

It is typical of Bain that he moved in leaps and bounds; from small, lively still lifes to something altogether more formidable. In his almost psychedelic canvas Ossian from 1944, Bain’s handling is so raw and intuitive that, as in his slightly earlier still lifes, it could easily be mistaken for naivety. But his image of the Celtic bard is so grand in scale, subject and imagination that Bain shakes off any accusation of naivety while retaining the wonderful expressive power of his handling. It is a sophisticated artistic statement as well as an exhilarating piece of painting. Few images in Scottish art burn with the power of such shocking colour, applied with dazzling vitality: the result is electric. It is quite remarkable that Ossian was painted during the war years in Glasgow, but it is typical of Bain’s work of the time that he felt able to tackle serious subjects – a portrait of a figure associated with the Celtic Revival, in this case – in an idiom which appears strikingly individual and unselfconscious. Bain confirms as much in describing the creation of Ossian: he said it resulted from a “sudden realisation that I was able to say something of my own in paint, and I didn’t care whether anyone liked it or not” [15].

Donald Bain. Ossian. Oil on canvas. 76 x 49 cm. 1944. Courtesy of Perth Art Gallery (Culture Perth and Kinross Museums and Galleries).

The figure of Ossian captured the imagination of the western world in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, becoming a central figure in the Romantic movement and the Celtic Revival. The legendary Celtic bard was the purported author of a great cycle of Gaelic poems penned, in reality, by the writer James McPherson. McPherson’s literary hoax seduced artists as great as Ingres and Ossian became an influential force in the development of Romanticism internationally, while remaining a distinctly Scottish figure who appears frequently in the visual culture of the time [16]. In images such as John McWhirter’s c.1882 painting Ossian’s Grave, for instance, Ossian is rooted literally in the Scottish soil, and tied figuratively to the peculiarly Scottish iteration of the Romantic landscape genre, under the purple heather and the mist-swaddled mountains.

John MacWhirter. Ossian’s Grave. Oil on canvas. 207 x 146 cm. Courtesy of Salford Museum and Art Gallery.

Bain’s Ossian is a long way indeed from McWhirter’s Ossian. While McWhirter and many others swept the Celtic hero up in the melodrama of Scottish Romanticism, Bain has chosen to treat his recognisably Scottish subject in a strikingly un-Scottish manner. As in Still Life with Mallet, Bain breaks cleanly with tradition. He has created an inspired and unique work of art which also reflects some of the currents of modern, progressive painting which were active in Europe at the time. Indeed, as William Hardie noted, Ossian has striking similarities to work by those artists associated with the COBRA group, brewing in continental Europe while Bain was at work [17]. Ossian could easily have been painted in the Parisian atelier of Bain’s dreams. In the painting, Ossian is evicted from his cave and electrified by the light of the continent: dazzled, perhaps, by the bright lights of the Folies Bergere. Ossian is both Bain’s own creation and an identifiably Scottish picture in its own way, but it also shows an artist yearning for Paris; in Ossian, we can sense Bain’s eagerness to forge a dialogue with the French capital, just as we can sense the presence of the great Francophile J.D. Fergusson, who loomed large in Bain’s mind.

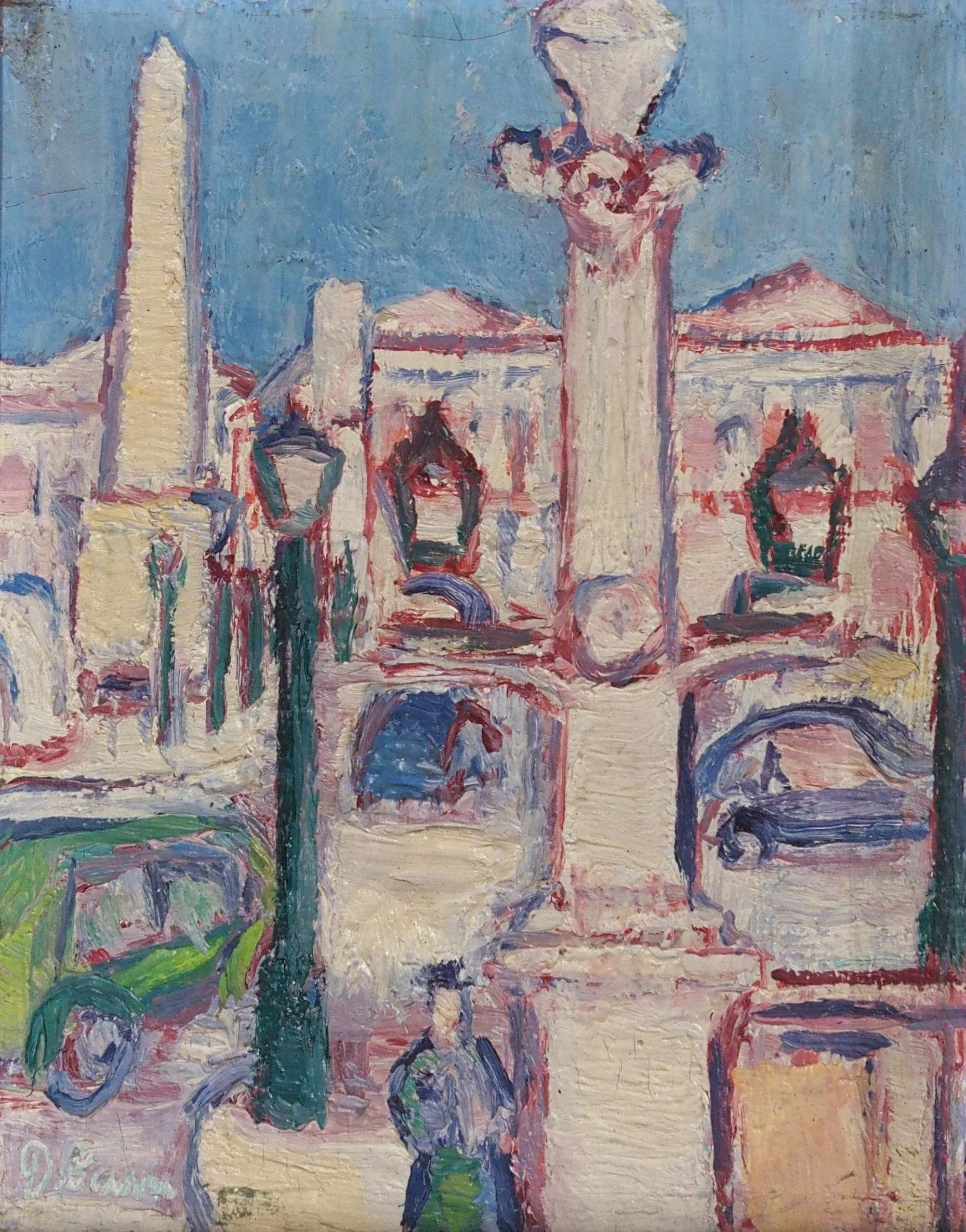

While Bain worked to develop his painting in line with his own personal vision, France was never far from his thoughts. He had visited Paris as a tourist in 1928 and returned for the first time as an artist in 1946 [18]. Over the coming decades, he spent extended spells in the capital and in St Paul de Vence in the south, benefitting greatly from Fergusson’s contacts and financial support [19]. He endured a great deal of hardship in France and his relatively few artistic successes were hard-won; nevertheless, nothing appeared to alter his view that “Paris is the centre of the world and the only place for me or for any artist, not for pastiche makers” [20]. Even in his later, generally weaker landscape works, Bain avoids pastiche like the plague: the individuality of his style is unmistakable, even if much of his work drifts towards the decorative. It is true that there are moments in Bain’s life where his work came close to the work of others: his 1946 painting of Paris’ Place de la Concorde is reminiscent of Fergusson’s work, particularly in its palette, though the modelling of the forms and the tactility of the paint, not to mention its distinctive murkiness, suggest a different manner altogether [21]. For all that it shows Fergusson’s influence, even Place de la Concorde stands up as an accomplished and unique work in its own right.

Donald Bain. Place de la Concorde. Oil on canvas. 23 x 15cm. 1946. Courtesy of Great Western Auctions.

Unlike Place de la Concorde, Bain’s image of Ossian cannot be related to Fergusson’s work in stylistic terms, but the influence of the elder artist is notable in other ways. Fergusson’s role in shaping Bain’s conception of the Celtic world is important in the story of Ossian’s creation. Both artists shared an enthusiastic identification with their Highland ancestry; more broadly, the Celtic world. Fergusson discussed his thoughts on the Celtic connection at length in his 1941 book Modern Scottish Painting, championing the Auld Alliance between Scotland and France; two “Celtic” peoples with a shared racial ancestry and aesthetic inheritance. “French culture was founded by the Celts, and invasions have not changed the fundamental character of the French people”, Fergusson wrote. “Every Celt feels at home in France. The “Espirit Gaulois” – ‘the Celtic Spirit’ - still exists” [22].

These words were surely ringing in Bain’s ears as he painted. The image of Ossian undoubtedly came naturally to Bain, who was fiercely proud of his heritage, but Fergusson’s role in articulating the nature of the Celtic world must have opened up a new avenue of enquiry, and it would appear Bain explored it with enthusiasm. Fergusson’s suggestion that a genuine identification with one’s Celtic heritage could be predicated on a love for both Scottish and French culture seems to have validated and encouraged those Francophile tendencies of Bain, a proud Scot. The evidence for this would appear to be braided through Bain’s contributions to Scottish Art and Letters, the journal which allied Scotland to modern cultural developments, particularly in France [23]. The proof also appears in a series of paintings from the mid-1940s, which show Bain identifying elements associated with Scottish culture, like the image of Ossian, and treating them in a manner which reflects the art of France, particularly that of the Paris scene. A small number of ambitious paintings show that this fusion of elements could be very potent indeed.

Donald Bain. The Rising of 1745. Oil on canvas. 91 x 76cm. 1945. Courtesy of Great Western Auctions.

The Rising of 1745, painted in the bicentenary of the failed Jacobite uprising, is an inspired attempt to summon a modern Celtic spirit on canvas. It concerns a central moment in Scottish history which was swept up in the tide of Romanticism in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. But as in other works, Bain treats the episode in terms which are alien to the Scottish visual vocabulary. Here, it is as if the old, Romantic depictions of the rising have been torn up and reassembled in a colourful and discordant collage: Bain creates a refreshingly abstracted image of the drama which shows Scottish history viewed through the kaleidoscopic lens of modern French painting. The Rising of 1745 suggests an awareness of a whole array of artists loosely associated with the Paris scene, including Constant Permeke, Filippo de Pisis and Umberto Boccioni. The painting is particularly reminiscent of Boccioni’s work, though the relationship between the Italian Futurist, dead by 1916, and the Paris scene of Bain’s day is tenuous: nevertheless, Bain’s conception of who and what constituted the “Paris scene” could be very flexible indeed, since for him, Paris was the centre of the artistic universe, around which all modern artists of note hung in orbit. The Rising of 1745 is a deliberate attempt to reflect the currents which were at work in modern painting and the work holds its own as an attempt to bind Scotland to “the centre of the world”; and for all of the influences at play, it remains a strikingly original and active piece of work, not a distant and dead pastiche.

Bain is one of many compelling figures in Scottish art to occupy a place somewhat on the periphery of the accepted narrative. Perhaps it is natural that these figures, for all of their significance, receive less attention than the “greats” of Scottish art. Fergusson is one such great, and his influence on Bain’s life and work is undeniable, but it is testament to something integral in Bain’s artistic personality that he was never tempted to imitate the master. Indeed, it was Bain’s reputation as a rule-breaker that Fergusson admired, and which fuelled the creation of a blazingly original body of work. This body of work was uneven in its quality, but the fact of the matter is no real detractor. William Hardie put it nicely in writing that “Bain was perhaps not a great painter, but he was a real painter, who produced a handful of great pictures” [24].

Bain was a real painter at heart, whose artistic engagement with France was the result of real, deeply-felt enthusiasm. The great deal of time he spent in France was relatively unusual for an artist of his day and particularly his background: it suggests yet another marker which distinguishes him as an artist of note. While Fergusson was an important force in facilitating trips, the proof of Bain’s brilliance is braided through a string of works which are clearly the result of a talented hand, a curious eye and an independent spirit.

Fergusson also played an important role in informing Bain’s thoughts on the Celtic world, but it was Bain’s artistic ingenuity and deep feeling for both Scotland and France which fuelled his wonderfully effective efforts to express something of the Auld Alliance in his work. Despite his place on the periphery, Donald Bain’s distinctive body of work points to something central in Scotland’s relationship with Europe. His strikingly individual oeuvre celebrates the Auld Alliance and confounds the notion that Scotland is damned as situated at “the bumpy north end of a severed limb of Europe” [25]. “Bain, Scotland’s artiste peintre”, bridges the gap, and he does so very much on his own terms.

Douglas Erskine

Notes

[1] Callum McKenzie, “A Personal View”, in Glasgow Print Studio, Donald Bain: Memorial Exhibition (Glasgow, 1980), p.6.

[2] William Hardie, An Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by Donald Bain (Dundee, 1973), p.3. Hardie first met Bain in 1968 and five years later, as Keeper of Art at Dundee Art Gallery, he organised an ambitious touring exhibition of Bain’s work. Hardie curated a further retrospective at The Collins Gallery, University of Strathclyde, in 2000. He wrote on Bain quite extensively and collected his work with enthusiasm.

[3] Clare Henry, “What French Connection Meant to Donald Bain”, Glasgow Herald, 7/10/80, page number unknown. Accessed 01/11/25 via the link: https://pixelbeans74679275.wordpress.com/1980-2/

[4] Unknown author, “Preface”, in Glasgow Print Studio, Donald Bain: Memorial Exhibition, p.3.

[5] Henry, “What French Connection Meant to Donald Bain”.

[6] Hardie, Donald Bain: A Scottish Colourist (Glasgow, 2000), p.57.

[7] These included the Diploma of Honour at the 1968 Annual International Italian Art Exhibition. Ref: Peter McEwan, Dictionary of Scottish Art and Architecture (Ballater, 2004) p.26.

[8] Hardie, Donald Bain: A Scottish Colourist, p.16. From a letter dated 27/06/47.

[9] Hardie, Gallery: A Life in Art (Glasgow, 2017), p.38. Hardie does not mention how Bain came to meet these figures, but it seems very likely that contact came through time spent around the Columbe d’Or. Certainly, Bain met Picasso at the Columbe d’Or and sketched his portrait in the famous hotel.

[10] Henry, “What French Connection Meant to Donald Bain”.

[11] Hardie, Gallery: A Life in Art, p.39

[12] Sheila McGregor, “‘L’Espirit Gaulois’: Fergusson’s Celtic Nationalism” in Alice Strang, J.D. Fergusson (Edinburgh, 2013), p.99.

[13] Fergusson and the New Scottish Group are also discussed in greater depth in Pierre Lavalle: Art as Life in art-scot 6. Donald Bain is also discussed.

[14] Hardie, Donald Bain: A Scottish Colourist, pp.3-4.

[15] Hardie, Scottish Art from 1837 to the Present (London, 1990), p.170.

[16] Ingres’ The Dream of Ossian, painted in 1813, hangs in the Musée Ingres Bourdelle in Montauban, France.

[17] Hardie, Scottish Art from 1837 to the Present, p.170.

[18] Hardie, Donald Bain: A Scottish Colourist, p.57.

[19] The support of Fergusson and his wife Margaret Morris, in all of its forms, was invaluable to Bain. Their generous financial support proved an important lifeline during Bain’s time in France. Their support is evident in the letters written by Bain, which can be accessed in the Fergusson Archive held by Perth Art Gallery.

[20] Hardie, Donald Bain: A Scottish Colourist, p.23. From a letter dated 27/07/55.

[21] Hardie points out that while Bain’s work appeared to recall Fergusson’s for a moment, so too did Peploe’s: “the artist is trying to see whether his own craft will produce the same aesthetic”. Ref: Hardie, Gallery: A Life in Art, p.178.

[22] See McGregor in Strang, J.D. Fergusson, pp.91-99.

[23] Scottish Art and Letters was published in five issues between 1944 and 1950, comprising a variety of high-quality literary and comment pieces and fine illustrations by Bain and other members of the New Scottish Group. Fergusson was Art Editor. Published by the notable Glasgow published William MacLellan, who also published a significant monograph on Bain in 1950.

[24] Hardie, Gallery: A Life in Art, p.38

[25] Edward Gage, The Eye in the Wind (Bristol, 1977), p.12

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Amy Fairley and Rhona Corbett of Perth Art Gallery for their help and support in the preparation of this text. Many thanks to the team at Perth, also, for allowing me to reproduce Painter’s Portrait and Ossian.

Many thanks to Luke Manning and the team at Great Western Auctions for allowing me to reproduce Place de la Concorde and The Rising of 1745. Both works were included in The William Hardie Sale, handled by GWA in August 2021.

Many thanks to Peter Ogilvie and the team at Salford Museum and Art Gallery for allowing me to reproduce Ossian’s Grave without charge. Their generosity is much appreciated.

This article is indebted to the efforts of William Hardie, who might have been the most enthusiastic promotor of Bain’s work to emerge after the artist’s death. This modest article is indebted to Bill’s hard work in preserving Bain’s memory.